The Science of Sushi

The Science of Sushi

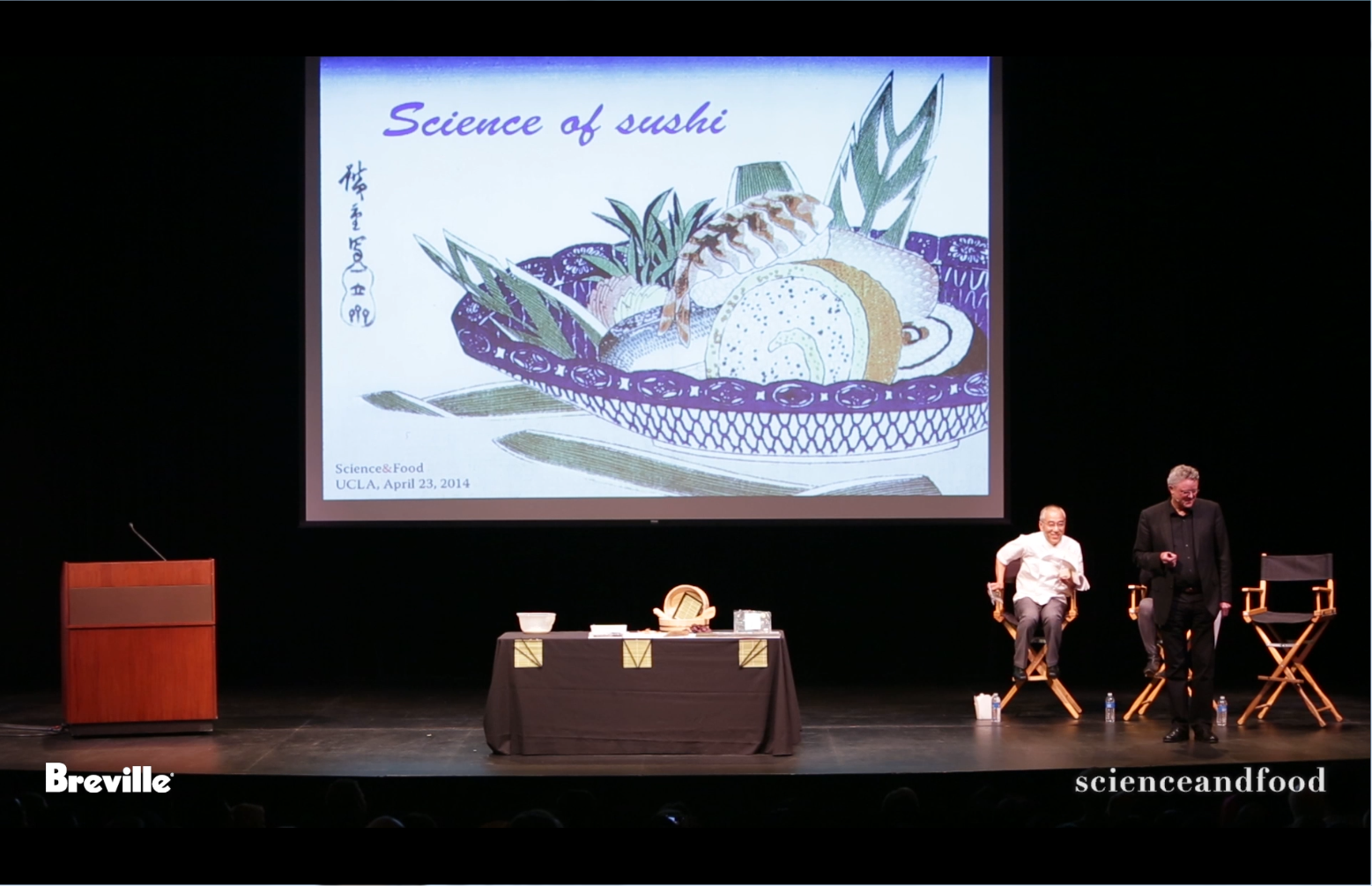

Featuring Dr. Ole Mouritsen and Morihiro Onodera

April 23, 2014

To kick off our 2014 public lecture series, Dr. Ole Mouritsen joined Chef Morihiro Onodera to satisfy our craving for sushi-related science. The duo explained everything from sushi’s early history to the starchy science of sushi rice. Watch the entire lecture or check out some of the shorter highlights below.

Ole Mouritsen on the history of sushi

“The history of sushi is really the history of preservation of food. . . . Throughout Asia, in particular in China and later in Japan, people discovered that you can ferment fish – that is, you can preserve fish – by taking fresh fish and putting it in layers of cooked rice. . . . After some time the fish changes texture, it changes taste, it changes odor, but it’s still edible and it’s nutritious. And maybe after half a year you could then pull out the fish and eat the fish. That is the original sushi.”

Ole Mouritsen on the science of rice

“If you look inside the rice, you have little [starch] granules that are only three to eight microns, or three t0 eight thousandths of a millimeter, big. . . . When you cook the rice, you add some water and the water is absorbed by the rice and [the granules] swell. And the real secret behind the sushi rice is that when they swell, these little grains are not supposed to break.”

Morihiro Onodera on examining the quality of sushi rice

“First what I do is I soak uncooked rice in water. . . . Sometime after 20 minutes it will start to break. . . . I take a sample to check to see if there are any cracks. . . . With good rice, which has less cracks or breaks, you’re able to feel the texture of each of the grains in your mouth, whereas with the lower quality rice you’re just going to get the stickiness [from the starch].”