Does your cheese taste of microbes?

In our unit on microbes and exponential growth, we learned about the role of microbes in altering flavor and mouthfeel. One of our favorite microbial foods is cheese: Cheese would just be spoiled milk if it were not for microbes.

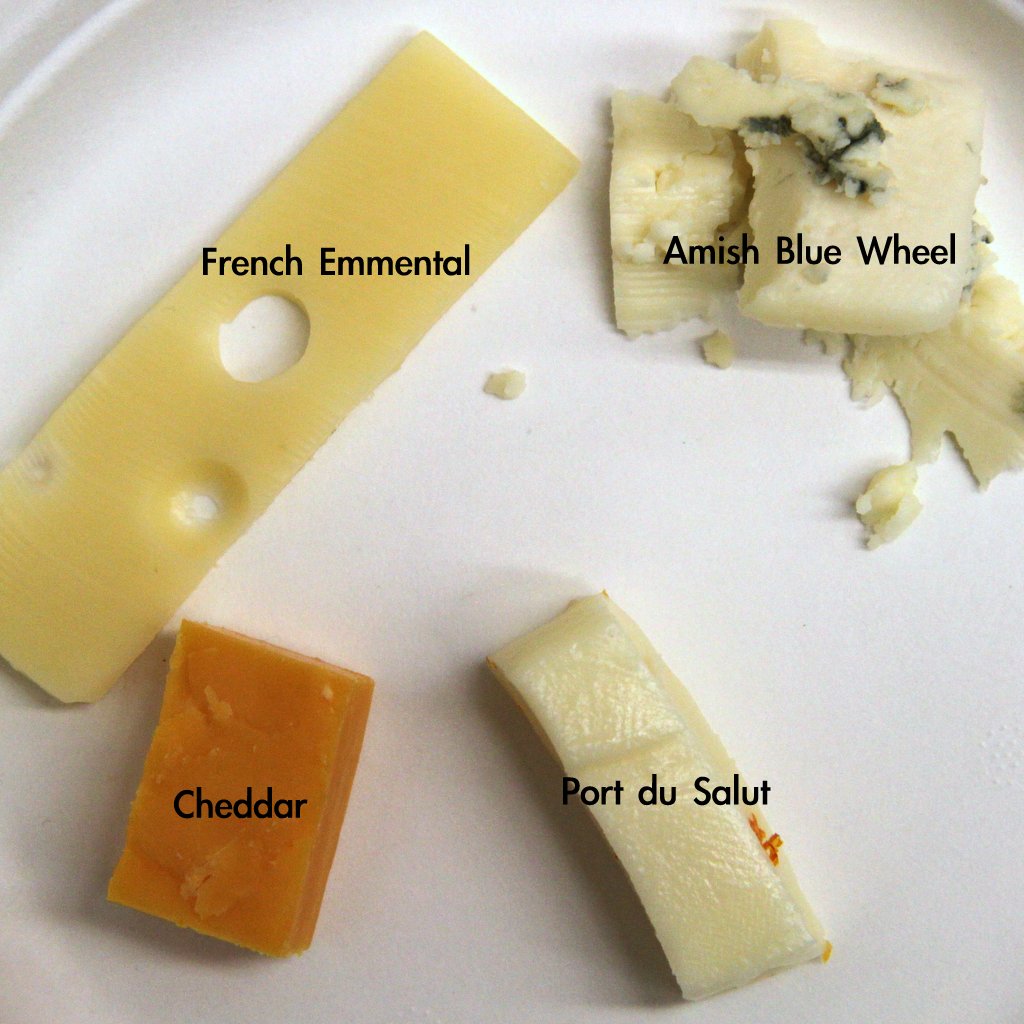

To kick off the class, we challenged the students with a taste test featuring four distinct cheeses:

A) Amish Blue Wheel

B) Emmental

C) Cheddar

D) Port du Salut

We also presented four different types of microbes, and a bit about natural habitats. Can you guess which microbe belongs to which cheese? Answers below.

1) Propionibacterium (inhabit human skin)

2) Penicillium mold (grow in cool, moderate climate; some species have blue color)

3) Brevibacterium (grow especially well without much personal hygeine)

4) Lactococcus lactis (grow well in acidic conditions)

ANSWERS:

A. 2 – Blue cheeses are inoculated with a strain of Penicillium mold, Penicillium roqueforti. Needles or skewers are used during the inoculation, which is why blue cheeses often have distinct veins running through them.

B. 1 – Emmental is a type of Swiss cheese, which is known for its holes. These holes are bubbles excavated by carbon dioxide, a byproduct of lipid breakdown by Propionibacterium freudenreichii, subsp shermanii. Its close cousin, Propionibacterium acnes, is linked to acne.

C. 4 – Cheddar is an example of a wide variety of cheese types that rely on Lactococcus lactis for the first stage of ripening. L. lactis uses enzymes to produce energy from lactose, a sugar molecule common in dairy products. Lactic acid is the byproduct.

D. 3 – Port du Salut is a washed-rind cheese. The cheese surface is wiped or washed down with a brine that promotes the growth of certain bacteria in the air. A smear of bacteria can be directly applied to the surface to nudge along the process. Brevibacteria linens is commonly used during this inoculation. Ever get a whiff of stinky feet from your cheese? Brevibacteria linens is the culprit, in the cheese and on real smelly feet.