Caffeine vs. Chocolate: A Mighty Methyl Group

Guest post by Christina Jayson

When my organic chemistry professor told me that the main molecular component of chocolate, theobromine, differs from caffeine only by the absence of one methyl group I was delighted: I could skip an entire step in caffeine metabolism, avoid the bitter taste of coffee, and increase my chocolate consumption. It seemed to make sense that as the caffeine I drank was metabolized by removing the methyl group, caffeine would convert to theobromine (the main compound of chocolate) (Figure 1). At the molecular level, a methyl group is a carbon with three hydrogens attached. It may seem simple, but a methyl group is an integral part of chemistry, biology, and biochemistry. For example, additional methyl groups can help a molecule to cross the blood-brain barrier and enter our brain – this barrier protects our brain from foreign molecules traveling in the blood that can be harmful [1, 2]. In the case of caffeine, it turns out that the extra methyl group on the molecule is what makes coffee active on our central nervous systems and an “energy stimulator,” while chocolate functions as a sweet treat and smooth muscle stimulator.

![Figure 1: During the metabolism of caffeine in the body, the methyl group (highlighted by the yellow box) is removed from caffeine and it is converted to theobromine (Modified from Wolf LK, 2013) [9].](https://scienceandfooducla.files.wordpress.com/2015/09/2.jpg)

Figure 1: During the metabolism of caffeine in the body, the methyl group (highlighted by the yellow box) is removed from caffeine and it is converted to theobromine (Modified from Wolf LK, 2013) [9].

So how do these two molecules act on different parts of the body, making coffee the substance of choice over chocolate bars when midterm season hits?

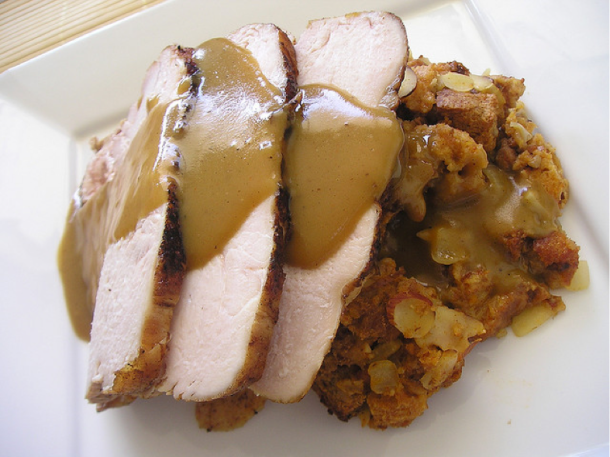

Caffeine is mostly derived from Coffea Arabica, or coffee beans, and seeds [3]. It is predominantly a central nervous stimulant, though it also stimulates cardiac and skeletal muscles and relaxes smooth muscles. Chocolate, or theobromine, is found in products of Theobroma cacao, or cocoa plant seeds (Figure 2). Much like caffeine, theobromine is a diuretic; however it mainly acts as a smooth muscle relaxant and cardiac stimulant [3]. While these two compounds have similar effects, the key difference is that caffeine has an effect on the central nervous system and theobromine most significantly affects smooth muscle [4]. In behavioral studies, caffeine intake improves self-reported alertness and mood over a period of 24 hours [5]. Theobromine produces mild positive effects in pleasure, but does not affect attention or alertness in moderate doses compared to caffeine [6].

Figure 2: Chocolate (left) is made from Theobroma cacao, or cacao plant seeds and contains theobromine (PC: Nic Charalambous). Coffee (right) is made from Coffea Arabica, or coffee beans, and seeds and contains caffeine (Photo credit: JIhopgood/Flickr).

But the true difference in the compounds lies at the molecular level. Both caffeine and theobromine belong to the methylxanthine chemical family. These chemicals act as stimulants of the nervous system, most notably by binding to adenosine receptors in the brain and thereby blocking adenosine from binding to the receptors [7]. Adenosine binding to adenosine receptors normally reduces neural activity, so the antagonistic action of caffeine and theobromine prevents this activity reduction (Figure 3). The increased energy and alertness that we connect to massive coffee consumption is due to the caffeine preventing your body from responding to signals that tell it to slow down or de-stimulate. Ever felt your hands jitter uncontrollably after too many shots of espresso?

![Figure 3: Caffeine molecules (C) compete with adenosine molecules (A) to bind to the adenosine receptors in the brain (Schardt, 2012) [10].](https://scienceandfooducla.files.wordpress.com/2015/09/4.jpg)

Figure 3: Caffeine molecules (C) compete with adenosine molecules (A) to bind to the adenosine receptors in the brain (Schardt, 2012) [10].

Experiments show the activity of caffeine on the nervous system is stronger than theobromine [7]. Caffeine and theobromine compete with adenosine to bind to the same adenosine receptor. Studies have shown that caffeine molecules are better able to compete with adenosine to bind adenosine receptors than theobromine – caffeine binds these receptors with two to three times higher affinity than theobromine [8].

To gain access to the different locations of the adenosine receptors throughout the body, the extra methyl group on caffeine ends up coming in handy. Because caffeine has three methyl groups instead of two like theobromine, it more easily crosses the blood-brain barrier. In crossing the blood-brain barrier, caffeine can act on the central nervous system. So while theobromine can act as a heart stimulant and smooth muscle relaxant, caffeine – boasting its extra methyl group – has access to the neurons of the central nervous system and can consequently enhance physical performance and increase alertness.

This means my master plan to forego coffee for chocolate won’t actually improve my alertness and energy to the same extent. However, indulging in chocolate flavored coffee may provide me with all the caffeine derivatives I need for a stimulating day.References cited

- Vauzour D, Vafeiadou K, Rodriguez-Mateos A, Rendeiro C, and Spencer JPE. The neuroprotective potential of flavonoids:a multiplicity of effects. Genes Nutr. 2008 3(3-4): 115–126.

- Svenningsson P, Nomikos GG, Fredholm BB. The stimulatory action and the development of tolerance to caffeine is associated with alterations in gene expression in specific brain regions. J Neurosci 1999. 19(10):4011–4022.

- Barile FA. Clinical toxicology: Principles and mechanisms. 2nd ed. Informa Healthcare Press. 2010. Ch 15, Sypathomimetics. 174-177.

- Coleman W. Chocolate: Theobromine and Caffeine. J Chem Educ. 2004. 81(8): 1232

- Ruxton C. The impact of caffeine on mood, cognitive function, performance and hydration: a review of benefits and risks. Nutr Bull 2008. 33:15–25.

- Baggot MJ, Childs E, Hart AB, de Bruin E, Palmer AA, Wilkinson JE, de Wit, H. Psychopharmacology of theobromine in healthy volunteers. Psychopharma. 2013. 228(1): 109-118.

- Kuribara H, Asahi T, Tadokoro S. Behavioral evaluation of psycho-pharmacological and psychotoxic actions of methylxanthines by ambulatory activity and discrete avoidance in mice. J Toxicol Sci. 1992;17:81-90.

- Daly JW, Butts-Lamb P, and Padgett W. Subclasses of adenosine receptors in the central nervous system: Interaction with caffeine and related methylxanthines. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 1983. 1: 69-80.

- Wolf LK. Caffeine Jitters. Chem & Eng News. 2013. 91(5): 9-12.

- Schardt, D. Caffeine! Nutrition Action Healthletter. 2012.

- Swift, C. (2014, June 2). Which is better for your brain? Beer or Coffee? You’ll never guess. [Web log post].

Christina Jayson is a recent UCLA Biochemistry graduate and currently a Ph.D. student in the Biological and Biomedical Sciences program at Harvard.

![Photo credit: Chris Swift, Rogers Family Co [11]](https://scienceandfooducla.files.wordpress.com/2015/09/5.jpg)