Fruit salad can be made throughout the year, but nothing beats a crisp fruit medley on a hot summer afternoon. There are very few limits on what can be a fruit salad ingredient. If the object in question is fruit, it can go in. Segregating fruit from non-fruit seems simple, but from a botanical point of view, classifying these sweet and juicy plant products gets complicated. But, if armed with knowledge and lemon juice, anyone can achieve this delicious and vibrant potluck offering.

Photo Credit: Jo Christian Oterhals (Flickr/jcoterhals)

A fruit is the structure of a plant that bears the seeds. A plant’s flower houses the female reproductive parts, namely the ovary, in the flower’s center. When fertilized, parts of the ovary develop into seeds, and the rest becomes the fruit.

Berries or Not?

The average person defines a berry as anything whose name ends in the suffix, –berry. But to a botanist, a berry is a fruit containing multiple seeds in its interior, embedded in the flesh of the ovary. This includes blueberries, tomatoes, eggplants, grapes, bananas, persimmons, and chili peppers [1]. A botanically-correct berry salad could be very savory; perhaps very spicy.

Blackberries, mulberries and raspberries all fall into the category of berry-imposters called aggregate fruits. Each little bump on a raspberry or blackberry is actually an individual fruit, as each is its own separate ovary, formed from one flower.

Botanically speaking, strawberries are actually not berries. Each pock on the fruit’s exterior is called an achene, and each achene is an individual fruit with a corresponding seed in the interior. The thing we call a strawberry is not a berry in the botanical sense, but rather an accessory tissue for an aggregate fruit (the achenes), formed from multiple ovaries of one flower. [2]

The “seeds” are actually achenes, and they are the true fruit of the strawberry plant. Photo Credit: Dome Poon (Flickr/MoHotta18)

Neither Pine nor Apple, and Not a Nut

A

pineapple is considered a multiple fruit. Whereas an aggregate fruit forms from one flower, a multiple fruit is the product of the fused ovaries of a cluster of flowers, thus each pineapple is one large composite fruit. Want to impress guests with a “multiple fruit” fruit salad? Your (somewhat limited) options include breadfruit, osage-orange, fig, and pineapple [3].

Coconut is Not a Nut

Technically speaking, a coconut is a fibrous one-seeded drupe. A drupe is a fruit with a seed enclosed by a hard stony shell, like a peach or olive. An unprocessed coconut has three layers. The smooth, green, outermost layer is called the exocarp. The next layer is the fibrous husk, or mesocarp, which surrounds the hard woody endocarp, which surrounds the seed. A supermarket coconut usually has been freed of its two outer layers. The part most likely found in a fruit salad are just shavings of the seed’s endosperm. This delicious white lining is meant to nourish the seedling coconut tree as it germinates [3].

Both the endosperm and the endocarp visible here. Photo credit: Su-Lin (Flickr/su-lin)

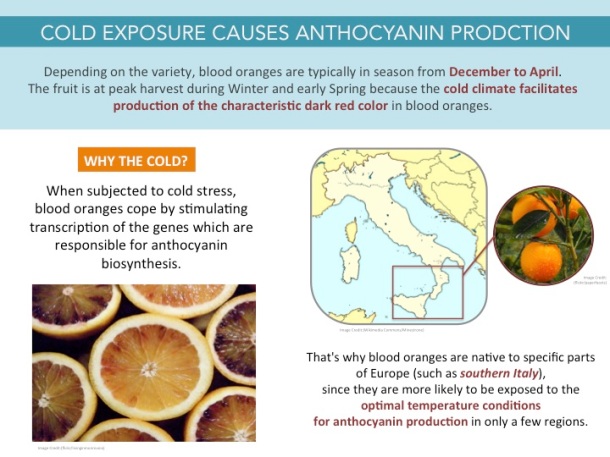

Keeping Fruit Salad Colorful

Apples, pears, and bananas notoriously turn an unattractive brown after dicing. This is because they contain an enzyme called polyphenol oxidase [4]. When the fruit is sliced, the enzyme is free to react with oxygen, as well as iron-containing phenols in the apple cells that had previously been kept separate. The products of these reactions are ugly, brown chemicals.

The middle of these apple cores have begun to brown. Photo credit: Stacy Spensly (Flickr/notahipster)

The key to preventing or slowing any enzymatic reaction is denaturing the enzyme. Heat will do the trick, as will reducing the fruit’s contact with oxygen by putting cut fruit under water or vacuum packing it. The simplest way to avoid browning is to apply lemon juice or another acidic substance on the cut surface. Enzymes can only function within a specific pH range, and acidic lemon juice will reduce the pH on the surface of the fruit. For those who fiercely oppose brown apples, try adding add sulfur dioxide [4], a chemical that acts as a preservative by binding to reactants in the fruit to interrupt the browning reaction. For anyone truly passionate about keeping their sliced fruits bright, upgrading to a sharper knife can help. A low quality steel knife may be corroded, and can make more iron salts available for the browning reaction.

References cited

- Lloyd, Robin. “Surprising Truths About Fruits and Vegetables.” Live Science. N.p., 22 July 2008. Web.

- “Aggregate Fruits.” Fruits Info. N.p., 2004. Web.

- “Is a Coconut a Fruit, Nut or Seed?” Library of Congress, 23 Aug. 2010. Web. 10 Aug. 2014.

- Helmenstine, Anne Marie. “Why Cut Apples Pears Bananas and Potatoes Turn Brown.” Chemistry.about.com. N.p., n.d. Web. 11 Aug. 2014.

About the author: Elsbeth Sites is pursuing her B.S. in Biology at UCLA. Her addiction to the Food Network has developed into a love of learning about the science behind food.

About the author: Elsbeth Sites is pursuing her B.S. in Biology at UCLA. Her addiction to the Food Network has developed into a love of learning about the science behind food.

Read more by Elsbeth Sites

About the author: Eunice Liu is studying Linguistics at UCLA. She attributes her love of food science to an obsession with watching bread rise in the oven.

About the author: Eunice Liu is studying Linguistics at UCLA. She attributes her love of food science to an obsession with watching bread rise in the oven.